When Milan’s Linate Airport introduced a “Faceboarding” facial recognition system — no boarding pass required, just a quick scan and you’re through — Italy’s data protection authorities reacted with horror. They suspended the system, citing “insufficient safeguards” for passengers who had not chosen to participate.

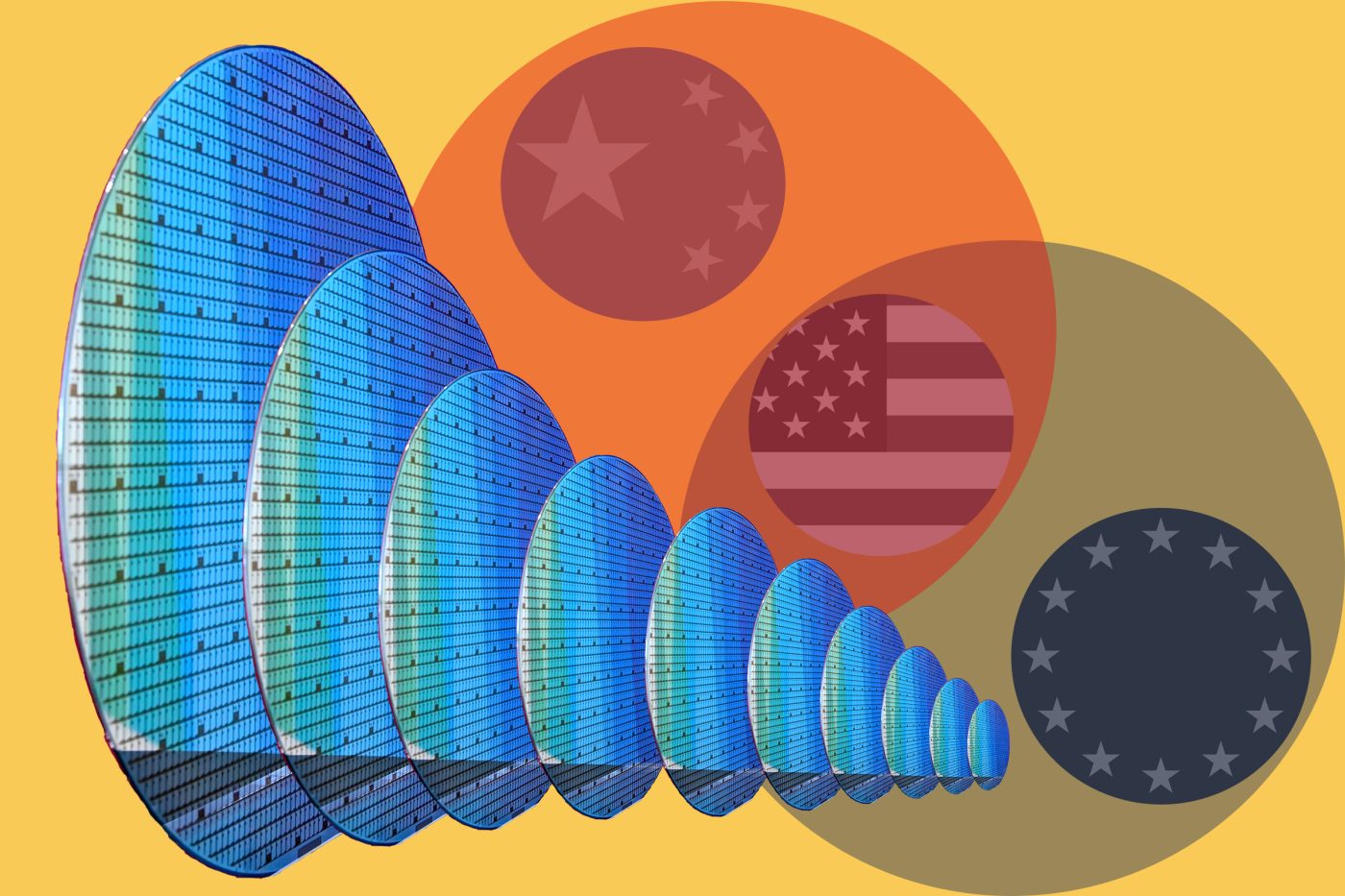

Both European and American approaches to the technology face a common challenge: how to move fast enough to stay competitive with China and other authoritarian states while moving carefully enough to preserve civil liberties.

The technology is advancing fast, driven by artificial intelligence. The market for facial recognition could reach $18 billion (€15.4 billion) by 2030, up from $8 billion today. Scanning a face is convenient compared to collecting fingerprints or encoding an iris. And many consumers like that convenience, whether it be for unlocking a device or boarding a plane where ID was previously required. But biometric data can also be abused, and governments and companies could abuse facial recognition to conduct mass surveillance. Studies show that facial cognition algorithms can be biased and inaccurate, more likely to misidentify people of color — and in particular, women of color.

In Europe, biometric systems must meet strict privacy requirements before they can operate. The US has no comprehensive federal law on facial recognition, though states are rushing to fill the void. Eighteen states have enacted statewide facial recognition technology regulations for law enforcement or broad public use, while three states have pending legislation under consideration or scheduled to take effect. The remaining twenty-nine states have neither active statewide FRT laws nor pending statewide FRT legislation.

China, for its part, has no qualms. It operates surveillance systems at a massive scale through projects like “Skynet” and “Sharp Eyes.” Beijing deploys more than 700 million cameras. In Shanghai, authorities are tripling the number of facial recognition cameras to allow tracking of 50 million citizens. A new National Identity Authentication Law went into effect on July 15, which encourages Chinese citizens to submit their true name and a facial scan, after which they would be issued a unique ID code used for all online accounts

Both the US and Europe want to avoid such mass surveillance.

Get the Latest

Sign up to receive regular Bandwidth emails and stay informed about CEPA’s work.

Europe is tightening regulations. The new AI Act imposes strict obligations on “high-risk” systems, including biometric identification. Data extraction from CCTV or the internet to expand biometric databases is prohibited, unless it is targeted and users consent.

Even voluntary facial recognition schemes face tough European scrutiny. Airport operators in the EU often position biometric boarding as an “optional opt-in” for EU citizens, but data protection authorities and regulators push back. Authorities require robust consent flows, data minimization, retention limits, and data protection impact assessments before these systems can operate.

Penalties are stiff. When US facial recognition company Clearview AI scraped billions of images from social media, breaching European GDPR privacy law, Dutch regulators imposed a €30.5 million fine and ordered the company to delete EU citizens’ images. Austrian privacy group noyb filed a criminal complaint in Austria last month that could subject Clearview executives to personal liability and even imprisonment.

The US approach to facial recognition technology is market first, regulation later. No comprehensive federal law governs commercial or law enforcement use of facial recognition. Regulation remains a patchwork of federal proposals and state and local statutes.

Surveillance use is increasing in the US. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials reportedly employ facial recognition technology to scan motorists’ photos to identify undocumented immigrants. The FBI compares driver’s license and visa photos against the faces of suspected criminals, according to a Government Accountability Office report.

Federal attention is growing. In Congress, various facial recognition bills have been introduced, including a recent proposal requiring the Transportation Security Administration to inform passengers of their right to opt out of face screenings. So far, though, all have stalled.

America’s fragmented approach allows experimentation and fast deployment but creates inconsistent protections. A facial recognition system legal in one state may be banned in another. A practice permitted for private companies may be restricted for the police. This patchwork creates uncertainty for both technology developers and citizens.

Courts are giving broad leeway to roll out facial recognition. When spectators sued New York’s Madison Square Garden for using facial recognition to block entry, a 2024 federal court dismissed the case.

Major US technology companies have implemented some voluntary limitations. Microsoft’s “Responsible AI” standards and product controls include strict access requirements for biometric features and documented risk assessments. Amazon announced a one-year moratorium in 2020 on police use of its “Rekognition” facial recognition product. The company later extended those restrictions indefinitely amid public pressure.

The Milan airport case arguably shows democratic oversight working. An independent regulator reviewed a biometric system, found it lacking in safeguards, and shut it down. No one was arrested. That model — transparent rules, independent enforcement, and accountable decision-making — is slow. It is messy. It creates compliance costs. But it separates the West from China.

William Echikson is a Non-resident Senior Fellow with the Tech Policy Program and editor of the online tech policy journal Bandwidth at the Center for European Policy Analysis.

Jensen Enterman spent the past year in Spain as a Fulbright scholar. She graduated from the University of Notre Dame with a Bachelor of Arts in Economics and Global Affairs and interned with the Tech Policy program at the Center for European Policy Analysis.

Bandwidth is CEPA’s online journal dedicated to advancing transatlantic cooperation on tech policy. All opinions expressed on Bandwidth are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

Explore the latest from the conference.

Learn More

Read More From Bandwidth

CEPA’s online journal dedicated to advancing transatlantic cooperation on tech policy.

Read More

link